Attention iOS users: You will not be able to view tables on this page without Adobe Flash Player, which is not supported by iOS. You can click on links to tables, or install a web browser with Flash support, such as Puffin (free download from Apps Store but only 14 day free trial with Flash support).

Desktop users: You cannot print from the Scribd table format. For a printed copy, click on the link to the table and print from your browser.

Desktop users: You cannot print from the Scribd table format. For a printed copy, click on the link to the table and print from your browser.

Equine Nutrition (Stephanie Ohlemacher and George Lager)

Stephanie Ohlemacher is a Natural Hoof Care Practitioner/Clinician and practicing Registered Nurse with ICU/ER and OR surgery experience. She has studied hoof care under a number of prominent barefoot instructors, but ultimately her best teacher is the horse. She is a strong proponent of natural holistic trimming, utilizing natural horsemanship and alternative therapies. Ms. Ohlemacher has extensive experience (over a decade) with a wide variety of equines, including pleasure horses, miniatures to drafts, gaited horses, foals and mares, stallions, mustangs and donkeys. She uses conventional tools as well as abrasive trimming (angle grinder/flap disc), and offers basic and abrasive hoof care clinics at her farm near Elizabeth, Indiana. If you are unfamiliar with abrasive trimming, link to her video on YouTube. Email: sonaturalhoofcare@gmail.com

Stephanie with Stormy, one of 15 horses at her Spring Lake Farm near Elizabeth, Indiana.

This page will present some basic and easily implemented ideas on nutrition that will keep your horse, mule, or donkey happy and healthy. A number of equine health issues are related to nutritional imbalances. For example, ongoing equine studies show that balancing the diet can significantly benefit those equines diagnosed with acute and chronic laminitis (sometimes referred to as founder), insulin resistance (IR), equine Cushing's disease/syndrome and obesity. For a more information, refer to Dr. Eleanor Kellon's web site on nutrition.

Part 1. Carbohydrate levels in grass and hay forage

Part 1 was originally posted in May 2013 as an laminitis alert for equine owners in Harrison and adjoining counties in southern Indiana and Kentucky. Based on input from veterinarians and hoof care providers, there was a higher than normal incidence of acute laminitis cases last spring. It's that time of year again so take precautions for your at-risk horses. If this an emergency situation, go directly to Take-home message at the end of this page for further information.

Now that the cold weather has returned, you might want to read this article by Kellon (2014) on winter laminitis, particularly if your horse has had recurrent bouts of laminitis.

Now that the cold weather has returned, you might want to read this article by Kellon (2014) on winter laminitis, particularly if your horse has had recurrent bouts of laminitis.

Harrison County, Indiana lies just west of the Louisville Metro area. The county's southern half borders Kentucky along the Ohio River.

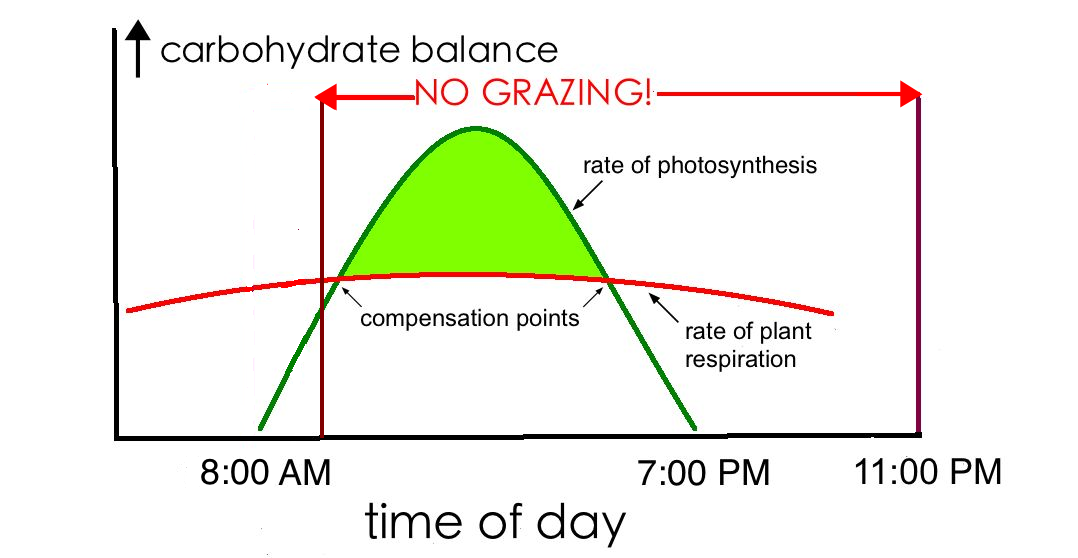

If your equine is at risk, high-carbohydrate (sugar) levels in grasses may trigger hoof soreness or laminitis, as diagnosed by a veterinarian. In most cases, the ideal time to graze IR equines, or those with chronic laminitis, is late night to mid-morning when carbohydrates are lower. The rate of carbohydrate production from photosynthesis during sunny days is greater than the rate of consumption from plant respiration, resulting in peak concentrations of carbohydrates in the afternoon (Fig. 1).

During warm, cloudy days, the rate of photosynthesis will be reduced and more of the stored carbohydrates will be consumed by respiration. After several successive cloudy days, sugar content may be low enough to graze at-risk horses in the afternoon.

During warm, cloudy days, the rate of photosynthesis will be reduced and more of the stored carbohydrates will be consumed by respiration. After several successive cloudy days, sugar content may be low enough to graze at-risk horses in the afternoon.

Figure 1. Stylized graph showing the relationship between carbohydrate storage (photosynthesis) and consumption (respiration) during a typical cloudless day in spring. The net gain in carbohydrates during the day is represented by the light green shaded area at the top of the bell-shaped curve. During the night carbohydrates are used for plant growth. At the compensation points, rates of photosynthesis and respiration are equal, i.e., carbohydrates produced are equal to those consumed. Carbohydrate-intolerant equines should not be grazed during "NO GRAZING" times when carbohydrate levels are highest (approximately 10:00 AM to 11:00 PM). The optimal "NO GRAZING" times are 10:00 AM to 3:00 AM (safergrass.org) but a 3:00 AM turnout is not practical for most horse owners.

A comprehensive treatment of carbohydrates in forage is given by Kathryn Watts at safergrass.org. Included on the safergrass web site is an article on "Pasture Management to Minimize the Risk of Equine Laminitis".

We are currently building a database of carbohydrate levels in grasses and hays in Harrison County, Indiana, in response to different environmental conditions (e.g., time of day, grass maturity, drought, overgrazing, sunny versus cloudy skies, dramatic changes in weather conditions, and soil nutrient levels). Some preliminary results are presented Table 1 below. Samples were collected based on the procedures recommended by Equi-analytical Laboratory ("Taking a Sample").

Pasture samples were placed in a conventional freezer at -17 C (0 F) within 30 minutes and shipped overnight with ice packs in insulated containers. Pelletier et al. (2010) have compared carbohydrate concentrations in forage samples using different drying procedures. Water soluble carbohydrates (WSC% in Table 1) determined after freezing spring growth (timothy) at -20 C (- 4 F) for 1 month followed by drying at 55 C (113 F) for 48 hours are ~10% lower than those obtained after freeze drying. This difference is comparable to errors associated with sampling and some nutrient analyses.

We are currently building a database of carbohydrate levels in grasses and hays in Harrison County, Indiana, in response to different environmental conditions (e.g., time of day, grass maturity, drought, overgrazing, sunny versus cloudy skies, dramatic changes in weather conditions, and soil nutrient levels). Some preliminary results are presented Table 1 below. Samples were collected based on the procedures recommended by Equi-analytical Laboratory ("Taking a Sample").

Pasture samples were placed in a conventional freezer at -17 C (0 F) within 30 minutes and shipped overnight with ice packs in insulated containers. Pelletier et al. (2010) have compared carbohydrate concentrations in forage samples using different drying procedures. Water soluble carbohydrates (WSC% in Table 1) determined after freezing spring growth (timothy) at -20 C (- 4 F) for 1 month followed by drying at 55 C (113 F) for 48 hours are ~10% lower than those obtained after freeze drying. This difference is comparable to errors associated with sampling and some nutrient analyses.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Pasture samples

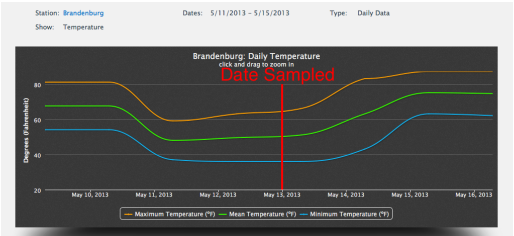

A cold front passed through the area two days before sample collection resulting in warm, sunny days and freezing nights (Fig. 2).

A cold front passed through the area two days before sample collection resulting in warm, sunny days and freezing nights (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Variation of maximum, mean and minimum temperature for the period May 10, 2013 to May 16, 2013 for the weather station at Brandenburg, Kentucky. Minimum temperatures at sample locations in southern Indiana near Central and Elizabeth were slightly less than 32 F with light frost. Red vertical line indicates sampling date. Image from archived weather history at weathersource.com.

Total sugar content is defined as ESC% + Starch% (dm) (Table 1, highlighted in red). A value less than ~10% is generally recommended for obese, laminitic, or IR equines. In a number of studies, WSC% + Starch% is used as an upper limit for sugar content of hays fed to laminitic equines; however, the fructan component of WSC% is probably not a high-risk factor in most pasture laminitic cases, particularly in the spring (more on this later). Fructan is not a sugar but a complex carbohydrate consisting of chains of fructose molecules.

"Pasture 1" was collected at 8:00 AM near Central, Indiana with the presence of a light frost (Fig. 3). Table 1 shows that total sugars are not excessively high, even though the sample was collected under environmental conditions that can cause "cold stress", i.e., decrease in plant respiration and increase in carbohydrate storage. Based on the carbohydrate level only, this pasture would be acceptable for grazing at-risk equines in the early morning. However, to avoid overeating and consuming too much carbohydrate, more limited access to this pasture may be required. The high fiber content NDF% of the mature grass is consistent with its lower carbohydrate content WSC% (dm) (Fig. 1, Watts 2008).

"Pasture 2" was collected at 5:30 PM on the same day from an overgrazed pasture near Elizabeth, Indiana (Fig. 3). This sample has twice the sugar content and is less fibrous (Table 1). The grass is short, which causes carbohydrates to concentrate at the base of the grass stems. Although the intake may be less, equines at risk should be removed from this pasture during the afternoon and provided low-sugar hay in a grass-free area, preferably a dry lot, or Paddock Paradise, rather than a stall.

"Pasture 2" was collected at 5:30 PM on the same day from an overgrazed pasture near Elizabeth, Indiana (Fig. 3). This sample has twice the sugar content and is less fibrous (Table 1). The grass is short, which causes carbohydrates to concentrate at the base of the grass stems. Although the intake may be less, equines at risk should be removed from this pasture during the afternoon and provided low-sugar hay in a grass-free area, preferably a dry lot, or Paddock Paradise, rather than a stall.

Figure 3. Photos of Pasture 1 (left) and Pasture 2 (see Table 1) taken about 2 weeks after sampling. The overgrazed pasture with short grass has twice the sugar content as the mature, ungrazed pasture. Note that seed heads in mature pastures are high in carbohydrates and should not be consumed by at-risk equines. Remove seed heads by mowing, or by grazing pastures with ruminants, or equines not at risk.

Instead of restricting turnout, consider a grazing muzzle (Fig. 4) during high carbohydrate times. Daily movement is NECESSARY for symptom reversal of at-risk equines. Feed low-carbohydrate hay prior to placing grazing muzzle.

Figure 4. "Blue" suffered an acute laminitis attack during grazing high-sugar grass in overgrazed Pasture 2 (Fig 3). She was immediately removed from pasture, given phenylbutazone (bute) for pain relief, booted, and fed Dr. Kellon's Emergency Diet. The following day when she was showing less discomfort, excess hoof wall length was removed, preserving sole and frog integrity. After trimming, Blue was rebooted and confined to paddock with low-sugar grass hay. Several days later she was fitted with grazing muzzle, and released to a second pasture that was less grazed. Case study to follow with ongoing treatment and dietary adjustments.

Hay samples

Table 1 shows that sugar content in hay samples varies from 4.3 to 9.0%, a carbohydrate content acceptable for equines in good health. Hay 10 with 4.3% sugar contains a significant amount of timothy, a cool season grass noted for its low-sugar content. For more information on Purina Hydration Hay (Hay 11), go to Purinahorsehayblocks.com.

To reduce sugar content for at-risk equines hay can be soaked before feeding. Watts (2003) determined that the average decrease in WSC% (dm) after soaking 15 different hay samples for 30 and 60 minutes (82 F = 28 C) was 19 and 31%, respectively. A more recent study indicates that soaking hay for 20 minutes (46 F = 8 C) will reduce WSC% (dm) by ~5% (In depth:Hay soaking, TheHorse.com). In both studies, sugar loss on soaking was quite variable among hay samples. The greater losses observed by Watts (2003) probably reflect the temperature of the water, i.e., sugars are more soluble in hotter water, and the different harvesting techniques in the U.S. versus U.K., resulting in finer texture and greater surface area of U.S. hays (Longland et al., 2011, Veterinary Record, 06.11.2011). The greater the contact area between water and hay the easier it is to dissolve the sugars. Based on our limited database, most hays in Harrison County, Indiana do not require soaking before feeding.

More specific information on hay composition and texture, and environmental conditions during cutting and baling, will be included for the 2013 hay analyses.

Table 1 shows that sugar content in hay samples varies from 4.3 to 9.0%, a carbohydrate content acceptable for equines in good health. Hay 10 with 4.3% sugar contains a significant amount of timothy, a cool season grass noted for its low-sugar content. For more information on Purina Hydration Hay (Hay 11), go to Purinahorsehayblocks.com.

To reduce sugar content for at-risk equines hay can be soaked before feeding. Watts (2003) determined that the average decrease in WSC% (dm) after soaking 15 different hay samples for 30 and 60 minutes (82 F = 28 C) was 19 and 31%, respectively. A more recent study indicates that soaking hay for 20 minutes (46 F = 8 C) will reduce WSC% (dm) by ~5% (In depth:Hay soaking, TheHorse.com). In both studies, sugar loss on soaking was quite variable among hay samples. The greater losses observed by Watts (2003) probably reflect the temperature of the water, i.e., sugars are more soluble in hotter water, and the different harvesting techniques in the U.S. versus U.K., resulting in finer texture and greater surface area of U.S. hays (Longland et al., 2011, Veterinary Record, 06.11.2011). The greater the contact area between water and hay the easier it is to dissolve the sugars. Based on our limited database, most hays in Harrison County, Indiana do not require soaking before feeding.

More specific information on hay composition and texture, and environmental conditions during cutting and baling, will be included for the 2013 hay analyses.

Comparison of nutrient profiles for alfalfa-rich (Hay 6) and mixed-grass (Hay 7) hays

Table 2 below compares the nutrient profile for a alfalfa-orchard grass hay (Hay 6) and mixed-grass hay (Hay 7) from Central, Indiana. The well-known compositional differences between alfalfa-rich and mixed-grass hays are highlighted in blue. Although alfalfa is relatively low in sugars (Table 1), the higher protein content may not be appropriate for some horses, e.g., adult horses at average activity levels, or those with decreased renal function. Also note the high Ca/P and Ca/Mg ratios which must be balanced to ~2:1, as discussed in the following section.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Take-home message

1. Reduce sugars/carbohydrates for all equines to below 15%, and

at-risk equines to ~10% or less, including all carbohydrate-laden grains, feeds and treats.

2. Don't overgraze, or mow pastures too short. Both conditions produce plant stress and higher carbohydrate storage.

3. Manage grazing times for at-risk equines by restricting turnout to late evening-early morning hours.

4. Use grazing muzzles for at-risk horses when movement is necessary.

5. Feed low-sugar grass hay. If not tested, soak for ~1 hour.

6. Feed the Emergency Diet for laminitic equines, available through the Equine Cushing's Disease Insulin Resistance Group, Inc.

If you need immediate help, please contact:

Stephanie Ohlemacher,

S.O. Natural Hoof Care

cell: 502-387-7395

home: 812-969-3499

email: sonaturalhoofcare@gmail.com

and consult with your veterinarian.

Return to main page

1. Reduce sugars/carbohydrates for all equines to below 15%, and

at-risk equines to ~10% or less, including all carbohydrate-laden grains, feeds and treats.

2. Don't overgraze, or mow pastures too short. Both conditions produce plant stress and higher carbohydrate storage.

3. Manage grazing times for at-risk equines by restricting turnout to late evening-early morning hours.

4. Use grazing muzzles for at-risk horses when movement is necessary.

5. Feed low-sugar grass hay. If not tested, soak for ~1 hour.

6. Feed the Emergency Diet for laminitic equines, available through the Equine Cushing's Disease Insulin Resistance Group, Inc.

If you need immediate help, please contact:

Stephanie Ohlemacher,

S.O. Natural Hoof Care

cell: 502-387-7395

home: 812-969-3499

email: sonaturalhoofcare@gmail.com

and consult with your veterinarian.

Return to main page

Copyright George Lager, 2011-2014. All Rights Reserved (®)