The following article was originally published in the November 2013 newsletter from Hoegger Goat Supply (Hoegger Farmyard).

Introduction

There have been several blog articles published recently at Hoegger Farmyard that deal with the problem of copper (Cu) deficiencies in goats. As mentioned, this deficiency can be either primary, or secondary. The former is due to low Cu content of forage whereas the latter reflects the interaction between Cu and other chemical elements (minerals), such as iron (Fe), molybdenum (Mo) and sulfur (S). For these reasons, goats are usually fed Cu supplements to avoid a number of symptoms ranging from loss of pigmentation in hair coat to life-threatening anemia.

Copper deficiency is more pronounced in some regions than others and depends, in part, on the chemical composition of soil and underlying rocks. For example, on our farm in the karst limestone region of southern Indiana (Mitchell Plain), Cu concentrations in grass hay (~8 ppm) and commercial feed (~25 ppm) are adequate to meet the nutritional requirements of our dairy goats (ppm = parts per million, refer to Table 2). In contrast, high Cu supplementation (~1500 ppm Cu bolus) is required in the Adirondack Mountains (upper New York State) where thin, nutrient-poor soils have formed from glacial debris (tills) (refer to blog article by Rose Bartiss on copper deficiency in goats at Hoegger Farmyard).

In nutrient-poor soils, the roots of pasture plants, such as grasses and weeds, have some ability to selectively absorb and concentrate essential minerals. One interesting example from crop science is ragweed, which can have Zn concentrations seven times greater than those of corn leaves at tassel! In other words, as most gardeners know, weeds can deplete soils of nutrients. Goats are great “weedeaters”, so why not use organized plots of certain pasture weeds to supplement minerals in their diet? The trick is to find the right weeds. You want the nutritive value but you don’t want to propagate a host of noxious weeds that will upset your neighbors and the local extension agent.

Our pastures consist of a variety of weeds, including chicory, dandelion, broadleaf dock, common lambsquarters, common and giant ragweed, narrow-leaved (buckhorn) plantain, bull thistle, redroot pigweed, Sericea lespedeza and Jerusalem artichoke (http://oak.ppws.vt.edu/weedindex.htm). We have seen our goats browse all of these weeds until heavy frost near the end of October. We decided to determine macronutrients and micronutrients for some of the more palatable (and controllable) weeds and see if we could find several good candidates for our pasture plots. Let’s face it, goats are browsers and were not meant to graze grass pastures. Their feeding habits and nutritional requirements are more similar to deer than to other domestic ruminants.

Background

The idea to use weeds as alternative pasture plants is not new. Harrington et al. (2006) (http://www.nzpps.org/journal/59/nzpp_592610.pdf) briefly reviewed the pertinent literature and determined the mineral composition of several of the weeds noted above. The weeds were sampled from both conventional and organic plots on the Tokomaru silt loam (soil texture with high proportion of silt to sand and clay) within the Dairy Cattle Research Unit of Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. Both plots were fertilized within the last 12 months (refer to Harrington et al. for more details). Results indicated that common weeds have elevated concentrations of several different nutrients relative to conventional pasture forage, such as perennial ryegrass and white clover.

Methodology

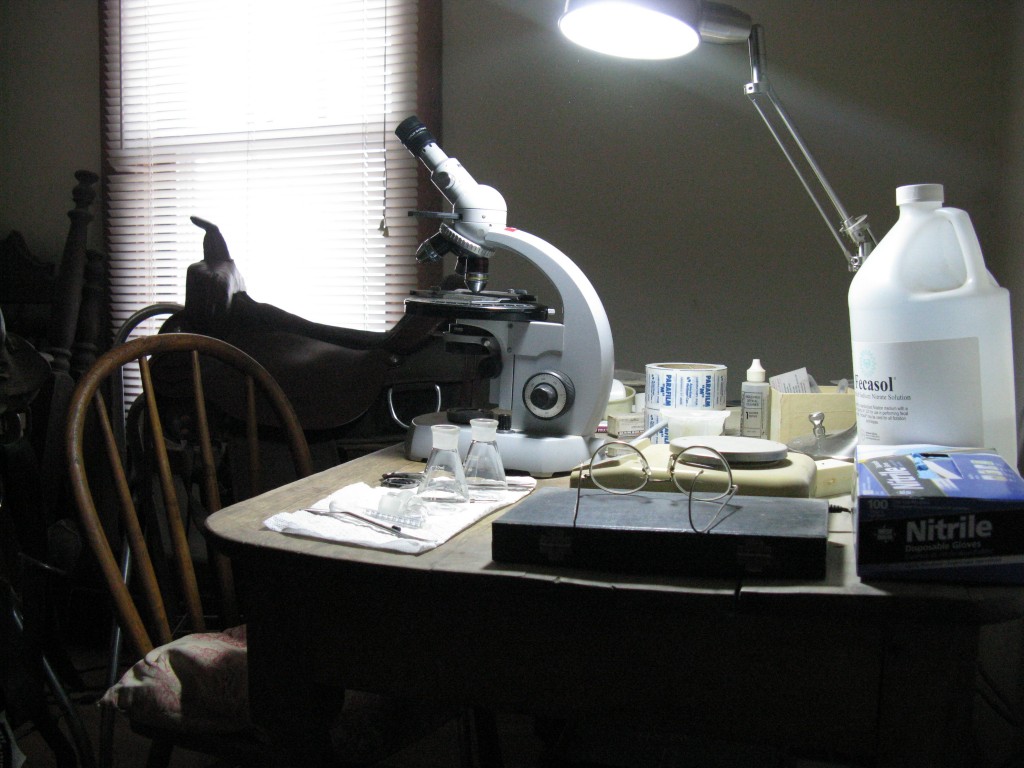

The weeds in our study were collected in the same pasture areas as those browsed by goats. Pasture soils are predominantly silt loams (Crider series), which developed from weathered limestone (calcium carbonate) and loess (windblown sediment). Only the upper ~15 cm (6 in) of each plant was included in the samples (~100 g = 0.22 lb), mimicking as closely as possible the feeding habits of our goats. At this time of year (August-September), some of the weeds had very fibrous stalks with seed heads, e.g., ragweed, lambsquarters and pigweed. With the exception of chicory, only one sample of each weed was collected (no replicates). Chicory was sampled twice to evaluate the nutrient distribution between basal leaf rosette (vegetative state) and flowering stalk (reproduction stage). Hay samples consisted of cores taken from 12-20 representative bales. No fertilizers other than composted horse manure were applied to pastures (www.mitchellplainfarm.com/on-farm-manure-and-mortality-composting.html). Samples were analyzed by the Dairy One Forage Laboratory, Ithaca, New York, using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

Results and Discussion

Some of the results from Harrington et al. (2006) and our new analyses of weed and hay samples are compared below in Tables 1 and 2. Note that the unusually high Na concentrations in the New Zealand data are due to atmospheric deposition of sea salt. Several of the weeds analyzed in this study are enriched in both macronutrients and micronutrients relative to grass and legume hays, consistent with the study by Harrington et al. (2006). For example, Ca in ragweed and Jerusalem artichoke is ~50% higher than that in alfalfa–rich hay (Table 1). Zinc, the most deficient micronutrient next to Cu, is enriched in all weeds with the exception of Sericea lespedeza and redroot pigweed (Table 2). The highest Cu concentrations are found in ragweed, chicory and Jerusalem artichoke. These weeds are also good sources of P, Mg and K.

Pigweed, which is a very popular browse among our goats, has about two times the P and Mg content as alfalfa-rich hay. However, pigweed has the potential to accumulate high nitrate (NO3–) concentrations during extreme environmental conditions, such as drought. After ingestion, nitrate is converted to nitrite (NO2-), which interferes with hemoglobin’s ability to carry oxygen to tissues. The nitrate concentration measured for pigweed in this study was ~0.25% (2500 ppm), which is below the maximum level recommended for cattle (<0.6%) (Radostits et al., Veterinary Medicine, 9th ed., 2000). Relatively high nitrate concentrations can also occur in lambsquarters, a nutritious source of Mg, K and Mn. Because goats are browsers and there is a large diversity of weeds in our pastures, they don’t spend much time feeding on one plant. As a result, they can avoid potential toxic effects and still make use of nutrients in both pigweed and lambsquarters.

Sericea lespedeza is high-tannin forage that has been shown to be effective in controlling internal parasites in goats (http://www.scsrpc.org/SCSRPC/Files/sericea_lespedeza.pdf). It’s not a favorite of our goats but they will browse the tops when confined to pastures dominated by this weed. Lespedeza is a legume and, with the exception of Fe, has a nutrient profile very similar to the alfalfa-rich hay in Tables 1 and 2.

Keep in mind that the concentrations of plant nutrients do not necessarily reflect the actual amount absorbed by goats because of antagonistic effects, i.e., the negative effect of one mineral on another. For example, Mo and S can form insoluble compounds with dietary Cu in the rumen that “lock up” Cu and limit its absorption (www.dairygoatjournal.com/87-3/coppers_role_in_goat_health/).

Finally, let’s determine what weeds are best suited for our pasture plots. Ragweed is chock-full of nutrients but it is not a plant you want to propagate in your pasture. The alternative is to temporarily fence goats in ragweed areas, a common practice by goat owners. A similar strategy can be used for pigweed and lambsquarters. Sericea lespedeza is prolific in this area and is the major goat forage in one of our pastures.

The best choices for cultivation based on our study and the results of Harrington et al. (2006) are dandelion, chicory, narrow-leaved plantain and Jerusalem artichoke, all of which are good sources of Cu and Zn. Cu and Zn concentrations in chicory are highest when the plant is grazed in the vegetative state during leaf growth stage (Table 2). Although the leaves were sampled for analysis, tubers of Jerusalem artichoke are particularly tasty to animals (and humans) and enriched in vitamins and minerals. If you are going to expend all of this effort, why not plant weeds that are good for both you and your goats!

It is important to remember that this is a preliminary study. A more systematic, scientific approach with replicate samples would be needed to fully evaluate the use of weeds as nutritional supplements for goats. The nutrient concentrations in Tables 1 and 2 are specific to our local area and will vary depending on soil type, pasture fertilization and maturity stage of the weeds sampled.

Table 1. Macronutrients (% dry matter) in hays and weeds from Harrington et al. (2006) and samples collected near Central, Indiana. Values highlighted in bold are significantly higher than perennial ryegrass or white clover (statistical analyses by Harrington et al.).

|

Hay and Weed Samples from Harrington et al. (2006) |

||||||

|

% |

Ca |

P |

Mg |

K |

Na |

S |

|

Perennial ryegrass |

0.42 |

0.37 |

0.173 |

3.80 |

0.182 |

0.347 |

|

White Clover |

1.19 |

0.347 |

0.237 |

2.83 |

0.205 |

0.213 |

|

Chicory |

1.18 |

0.663 |

0.393 |

3.80 |

0.591 |

0.627 |

|

Narrow-leaved plantain |

1.77 |

0.480 |

0.253 |

1.97 |

0.618 |

0.530 |

|

Broad-leaved dock |

0.80 |

0.430 |

0.520 |

4.10 |

0.026 |

0.287 |

|

Californian thistle |

1.87 |

0.357 |

0.307 |

2.93 |

0.047 |

0.570 |

|

Dandelion |

0.96 |

0.570 |

0.353 |

3.43 |

0.420 |

0.393 |

Hay and Weed Samples Collected near Central, Indiana

|

% |

Ca |

P |

Mg |

K |

Na |

S |

|

Gamagrass |

0.41 |

0.26 |

0.20 |

1.37 |

0.016 |

0.18 |

|

Alfalfa (70%)/orchard grass |

1.38 |

0.21 |

0.31 |

1.58 |

0.009 |

n/a |

|

Ragweed (Giant) |

2.14 |

0.40 |

0.40 |

3.59 |

0.004 |

0.52 |

|

Lambsquarters |

1.28 |

0.30 |

0.50 |

6.60 |

<0.001 |

0.37 |

|

Chicory (flower stalks) |

1.28 |

0.38 |

0.26 |

2.08 |

0.020 |

0.31 |

|

Chicory (basal leaf rosette) |

1.49 |

0.55 |

0.32 |

4.65 |

<0.001 |

0.66 |

|

Narrow-leaved plantain |

1.86 |

0.29 |

0.25 |

3.26 |

0.003 |

0.45 |

|

Sericea lespedeza |

1.31 |

0.21 |

0.18 |

1.31 |

<0.001 |

0.19 |

|

Jerusalem artichoke (leaves) |

2.20 |

0.38 |

0.43 |

3.37 |

<0.001 |

0.32 |

|

Redroot pigweed |

1.28 |

0.49 |

0.63 |

3.22 |

0.002 |

0.24 |

___________________________________________

Note: To convert % to mass multiply by 10, e.g., gamagrass contains 0.41 % Ca = 4.1 g/kg Ca = 4.1 g/2.2 lbs Ca (3 kg hay = 6.6 lbs = 12.3 g Ca). Interpretation of chemical symbols: Ca (calcium), P (Phosphorous), Mg (Magnesium), K (Potassium), Na (Sodium), S (sulfur); n/a (not analyzed).

Table 2. Micronutrients (% dry matter) in hays and weeds from Harrington et al. (2006) and samples collected near Central, Indiana. Values highlighted in bold are significantly higher than perennial ryegrass or white clover (statistical analyses by Harrington et al.).

|

Hay and Weed Samples from Harrington et al. (2006) |

|||||

|

ppm = mg/kg |

Fe |

Cu |

Zn |

Mn |

Mo |

|

Perennial ryegrass |

151 |

7.9 |

22.0 |

99 |

0.64 |

|

White clover |

109 |

8.6 |

22.0 |

55 |

0.22 |

|

Chicory |

167 |

18.6 |

57.7 |

161 |

0.42 |

|

Narrow-leaved plantain |

182 |

15.1 |

37.7 |

109 |

0.27 |

|

Broad-leaved dock |

95 |

7.6 |

30.7 |

283 |

0.42 |

|

Californian thistle |

139 |

17.0 |

41.7 |

120 |

0.21 |

|

Dandelion |

115 |

14.2 |

37.0 |

93 |

0.373 |

Hay and Weed Samples Collected near Central, Indiana

|

ppm = mg/kg |

Fe |

Cu |

Zn |

Mn |

Mo |

|

Gamagrass |

239 |

8 |

25 |

57 |

1.6 |

|

Alfalfa (70%)/orchard grass |

218 |

10 |

20 |

70 |

0.7 |

|

Ragweed (Giant) |

144 |

16 |

72 |

79 |

0.5 |

|

Lambsquarters |

75 |

5 |

32 |

204 |

0.4 |

|

Chicory (flower stalks) |

90 |

12 |

41 |

24 |

0.8 |

|

Chicory (basal leaf rosette) |

117 |

18 |

72 |

36 |

0.8 |

|

Narrow-leaved plantain |

106 |

13 |

46 |

38 |

0.6 |

|

Sericea lespedeza |

98 |

10 |

27 |

65 |

0.8 |

|

Jerusalem artichoke (leaves) |

252 |

27 |

104 |

79 |

0.6 |

|

Redroot pigweed |

132 |

6 |

28 |

46 |

2.1 |

_____________________________________________

Note: ppm = parts per million where 1 ppm = 1 mg/kg, or 1 mg/2.2 lbs, e.g., 3 kg (6.6 lbs) gamagrass contains 8 mg Cu/2.2 x 6.6 = 24 ppm Cu. Interpretation of chemical symbols: Fe (Iron), Cu (Copper), Zn (Zinc), Mn (Manganese), Mo (Molybdenum).