I’m back with everybody’s favorite topic – worms, of course! I would put away that food you are munching on until you have finished reading this blog!

I want to share with you results from a simple comparative study that I carried out on common goat dewormers. It’s very unscientific but I thought it might be useful to some goat owners. As I mentioned in my previous goat blog, worms (parasites) are the number one problem affecting meat and dairy production worldwide, particularly in the Southern Hemisphere and Third World countries. It’s a major problem because goat worms are becoming resistant to all major groups of chemical dewormers (Kaplan 2013) The one parasite that’s the most serious threat is a guy called Haemonchus contortus, also known as the barber pole worm, or the blood worm. It makes a living sucking blood from the lining of your goat’s stomach and can cause severe anemia and, ultimately death, if not controlled.

Here’s an image of the culprit and some of its eggs captured with a fluorescence microscope. Ultraviolet (UV) light is causing the worm and eggs to “fluoresce”, or emit light in the visible portion of the spectrum. To give you an idea of scale, the long dimension of the eggs is about 100 micrometers, or 0.1 mm. This is a very ingenious application of the property of fluorescence to an important veterinary problem. I am sure that many of you have seen fluorescent mineral displays in geology departments and museums. It’s the same principle. Unlike some minerals, however, Haemonchus eggs are not naturally fluorescent. Therefore, the key is to find a chemical substance that (1) binds only to Haemonchus eggs in the fecal sample, and (2) fluoresces in UV light. In this case, the eggs are coated or “stained” with a plant protein (lectin) called peanut agglutinin. You can read a press release about the development and application of this technique at http://www.vet.uga.edu/pr/sheep-parasite.php.

Haemonchus contortus with several of its eggs as viewed with a fluorescence microscope. Photo credit: © 2009 The University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine.

Haemonchus is an example of a strongyle worm (small roundworm) found primarily in hotter, more humid climates. Unfortunately, its eggs cannot be distinguished from those of other species in this group based on size, or morphology (shape). The fluorescent staining method is a breakthrough in goat and sheep parasitology because it will now be possible to rapidly and inexpensively detect the presence of Haemonchus eggs and take the necessary steps to control this pathogenic organism (one worm can lay up to 10,000 eggs per day!).

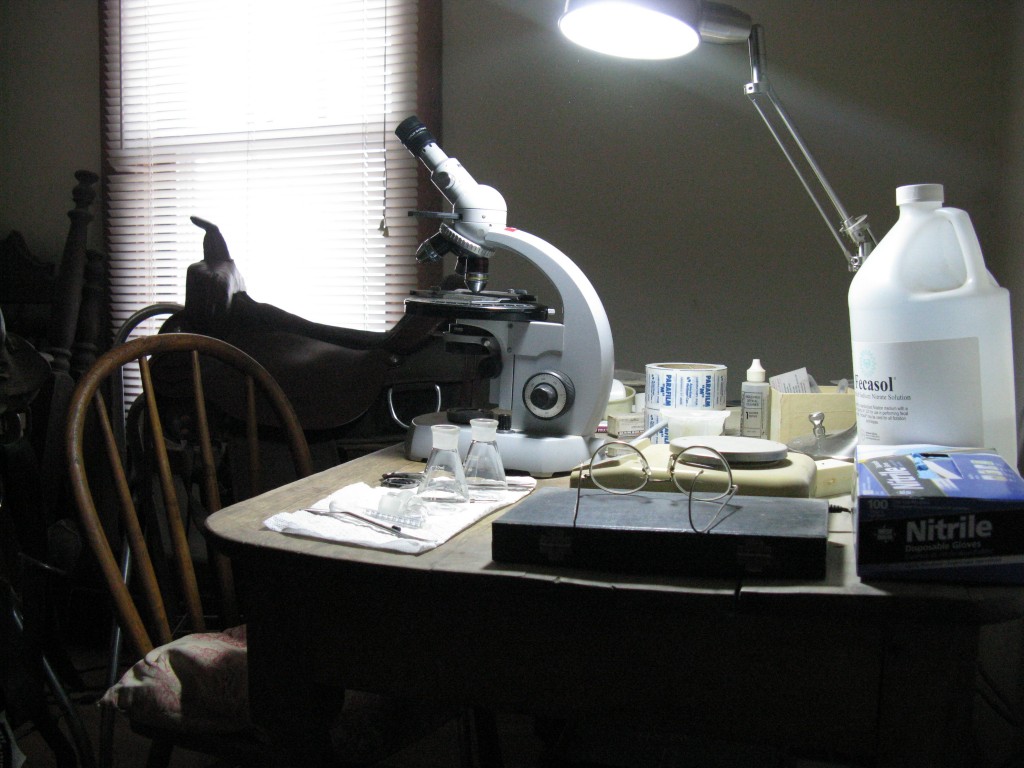

I have set up my own small parasitology lab at our farm. It’s easy to do, relatively inexpensive and avoids the high cost of fecal tests, currently about $50.00 per test (quantitative analysis) at veterinary clinics in our area. I also determine my own egg counts for my mustang horses. It’s easy to learn to identify the most common parasites. For example, web sites such as the Maryland Small Ruminant Page, provide a number of general parasitology links with images and tutorials.

This is a photo of my lab for determining fecal egg counts using the McMaster technique. Other than a microscope, you will need a standardized fecal solution (in this case, sodium nitrate, or Fecasol, Specific Gravity =1.20) for floating the eggs, McMaster slides, gram scale (optional), an assortment of glassware, a strainer and funnel, and some exam gloves. I use the Modified McMaster Technique described by Ray Kaplan DVM, PhD and James Miller DVM, PhD in the article Modified McMaster Egg Counting for Quantitation of Nematode Eggs. I changed their procedure slightly by including a step to filter out the solid fraction in the fecal solution. This makes it easier to extract the liquid fraction and load the McMaster slide. When interpreting the results of the McMaster technique, it is important to remember that egg counts might not reflect the actual number of worms present. Refer to The RVC/FAO Guide to Veterinary Diagnostic Parasitology for a list of the factors that can affect egg counts. This web site is also a good source for other information about fecal analyses of small ruminants.

The objective of my experiments was to determine the dosage of chemical dewormers necessary to reduce the population of internal parasites by at least 90-95% after 2 weeks. This is referred to as the fecal egg count reduction test (FECRT) in the scientific literature. There are number of different types of parasites in goats but only those eggs belonging to the strongyle group were counted. These are the most common eggs observed in fecal analyses of goats.

The current recommendation by parasitologists is to use one dewormer until FECRT < 95%, indicating significant parasite resistance (S. Mobini, DVM, Fort Valley State University, pers. comm.). In practice, the actual FECRT% considered acceptable in parasite control programs will depend on a number of factors, including the availability of dewormers with higher efficacy (If a drug has high efficacy, 0% of worms will survive the dewormer). However, as FECRT results approach 80%, parasite resistance and associated health effects will begin to increase more rapidly. For example, in sheep FECRT < 80% has a negative effect on lamb growth rate.

Included in this study were Rumatel® (Morantel Tartrate), Panacur®/Safeguard® horse paste, Moxidectin horse paste (Quest® Gel) and liquid (injectable CYDECTIN®), Ivermectin (horse paste) and Dectomax® (injectable). For the time being, I did not consider Levamisole (Levasole, Tramisol and Prohibit® Drench), or some of the other benzimidazoles, e.g., Valbazen, which is unsafe for pregnant animals in first trimester. Because of the small number of animals in my herd (normally four), I have not used the oral drenches, or suspensions, recommended for goats, which are more bioavailable than horse pastes. Oral drenches, such as IVOMEC® sheep drench (goat dosage = 6 ml per 25 lbs body weight), are usually sold in 1-liter (1000 ml) containers with a 1-year expiration date.

I normally don’t deworm until the level of anemia is equal to, or greater than, “3” based on the FAMACHA system (“5” being severely anemic). The FAMACHA test compares the color of the lower eyelid to a color chart to determine the level of anemia from Haemonchus infection. If you are not familiar with FAMACHA, or parasite control in general, you can read about it at the web site for the American Consortium for Small Ruminant Parasite Control (ACSRPC).

Summary of results from comparative study using McMaster egg counting technique

Rumatel® (Morantel Tartrate): Only dewormer approved by FDA as an additive to goat feed. Advantage is that there is no withdrawal period for milk. Recommended dosage on bag is 2 lbs. In fact, it takes 2 lbs daily for two successive days to achieve FECRT > 95% after 2 weeks. Good alternative if you are already feeding processed food or milking your goats. I recently switched to Goat Care-2X medicated pellets (generic Rumatel® 88). Same stuff but more concentrated so one treatment (4 oz per 50 lbs body weight = 88 gm Morantel Tartrate per 100 lbs) will produce similar results for FECRT.

Panacur® (horse paste): One dose at 2-3 X body weight is ineffective (well known from goat literature). Three successive daily doses at 2-3 X body weight will reduce FECs by > 90% after 2 weeks (for any horse owners out there, this is the Panacur Powerpack for goats!). Panacur® and Safeguard® are the same drugs sold under a different label (Fenbendazole). The recommended goat dewormer is Safeguard®/Panacur® suspension (see ACSRPC table of anthelmintic dosage and withdrawal times below).

Moxidectin (Quest® Gel horse paste) versus liquid (injectable CYDECTIN®): FECRT for both dewormers was > 90% after 2 weeks. Dosage for paste is 2 X body weight, that for liquid only 1 X, as recommended by ACSRPC. Downside to using the injectable liquid is cost for a small herd — about $110.00 for 200 ml. Philosophy behind using the liquid is that less is required (it has a longer residence time, or persistence, in the animal’s system) so parasite drug resistance will develop more slowly. As it turns out, the injectable form of Moxidectin (CYDECTIN®) is no longer recommended for use by the ACSRPC because of its greater withdrawal times (120-130 days) for consumption of meat. In addition, a recent study indicates that Moxidectin has a higher efficacy when administered orally in cattle (CYDECTIN® Drench) rather than injected subcutaneously, or applied topically (pour-on). Oral use of pour-on CYDECTIN® is not recommended for goats.

Ivermectin (horse paste) and Dectomax® (injectable) (avermectin group): Not effective in significantly reducing FECs for my small herd (FECRT << 80%). Neither the Ivermectin (IVOMEC®) sheep drench, or injectable ivermectin (IVOMEC®), administered orally or subcutaneously, were used in this limited study. Both routes of injectable ivermectin are considered (extremely) extralabel because the IVOMEC sheep drench is available. In addition, the formulation (solution of chemical substances plus active drug) for the oral drench is more bioavailable than ivermectin injectable given orally (Patty Scharko, DVM, Clemson University, pers. comm.). For those of you with lactating dairy goats, note that ivermectin injectable has a 40-day withdrawal time for milk (FARAD Digest 2000).

For reference, anthelmintic dosage and withdrawal times for goats are given on the ACSRPC web site. Note that Rumatel® 88 listed in the footnote to ACSRPC table has 0 days milk withdrawal time for 88 gm/100 lbs body weight dose (refer to withdrawal charts in Compendium of Veterinary Products 2014).

A few concluding remarks about the drug class of macrocyclic lactones (MLs), which includes two closely related chemical groups – the avermectins and milbemycins. Ivermectin and Doramectin (“Dectomax®”) are avermectins whereas Moxidectin is a member of the milbemycin group. Ivermectin and Moxidectin have a longer persistence in the body, which means that these dewormers can persist in lethal concentrations for an extended period of time. Relative to Ivermectin, Moxidectin provides a greater persistent period and a greater efficacy against resistant worms.

Keep in mind that Ivermectin has been used extensively in goats since the 1980s so one might expect a greater parasite resistance to this drug. Moxidectin is a more potent drug and the last of the MLs to be introduced. Therefore, parasite drug resistance should develop more slowly. Unfortunately, Moxidectin is no longer effective in controlling parasites in many sheep and goat farms in the eastern and southern U.S. (Kaplan 2013). This trend will continue if we don’t make judicious use of dewormers, and employ effective pasture management practices that disrupt the life cycle of parasites.

So far we have only talked about chemical dewormers. There are other alternatives such as herbal remedies and pasture plants but how effective are they in controlling internal parasites? More on this topic at the ACSRPC web site.

At present, we are trialing the herbal product Verm-X (certified organic, available from ebay) and pasturing our goats in areas where the tannin-rich plant Sericea lespedeza is particularly abundant. For a nutrient profile (major and trace minerals) of Sericea lespedeza (a legume) link to my blog article on Pasture Weeds as Mineral Sources for Goats.

As a disclaimer, I need to mention that I am not a veterinarian and cannot provide medical advice for your goats. All the information presented here is based on work with my dairy goats, the ACSRPC web site and what I have read in the scientific literature. Updated July 17, 2014